Through the 2021-22 academic year, Lucy Panesar worked with people from UAL, Wikimedia UK and the South London Gallery to continue investigations into events like the 1911 Festival of Empire and to address how these events are represented on Wikipedia. This included UAL in-curricula and extra-curricula events and workshops to prompt and support students and staff to edit Wikipedia pages related to London’s colonial her/histories and legacies, through an anti-racist, decolonial lens. It has also included an exciting collaboration with the South London Gallery’s Art Assassins for a project called Places Never Seen.

Places Never Seen: A youth led, digital exploration of the 1911 Festival of Empire

Places never seen: A youth led, digital exploration of the 1911 Festival of Empire was initiated in 2021 for this Audience Agency call and was supported by their Digitally Democratising Archives project funded by the DCMS and the National Lottery, as part of The National Lottery Heritage Fund’s, Digital Skills for Heritage initiative. The project ran between September 2021 and March 2022 and enabled the Art Assassins to develop archival research and digital storytelling skills through online platforms like Wikimedia and FrameVR. Paul Crook and Tommie Introna from the South London Gallery led the project planning and delivery, including weekly Art Assassins workshops. Lucy Panesar oversaw the project planning and brokered partnership work with Wikimedia UK and UAL’s Creative Computing Institute, plus input from Invisible Palace, The National Archives and the Black Chiswick through History project.

Reflections from Places Never Seen researchers

Harriet Vickers and Sam Baraitser-Smith, recent alumni of the Art Assassins programme, were recruited as young researchers on the project to investigate the 1911 Festival of Empire and deliver workshops with the Art Assassins. Harriet writes about her experience of this below:

I’m Harriet and I’ve been a researcher for the Places Never Seen Project. In addition to my research role, I co-led workshops with Sam for the Art Assassins, in which we presented our research, did clay sculpting and also supported the Art Assassins in their digital workshops. In this blog post I will outline what we did and provide my general insights into the project!

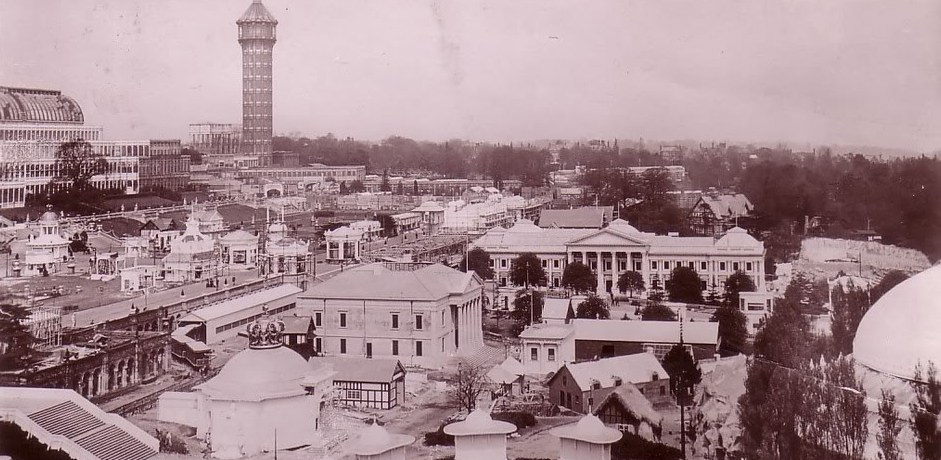

Before we began our research, we listened to voice notes of the Art Assassins’ questions about the project so far. This provided a great starting point. The project seemed like a mammoth task at first, so we focussed on points of interest to inspire our research. We came to the resolution that the Empire affected millions of people worldwide but within the festival we see the effect of the Empire on Britain itself and how the organisers wanted the Empire to be perceived. We see the idealised colonial settings (in the diamond mine and tea plantation scene on the All Red Route) and scaled down versions of political colonial buildings from different colonised countries. We also see the might of British industrialisation represented in the railway that connects the “all red route”. Like the festival of Empire, other contemporary festivals such as “The Great Exhibition” displayed the wealth, resources, and materials that the Empire provides for Britain. Essentially, the festival is the Empire from- the British point of view. We wanted to understand who had been excluded from this narrative and see if we can illuminate these voices.

In addition to presenting research about the composition of the festival itself, I shared details of the perception of the festival as well as its purpose in the wider context of the British Empire at this time. I was really trying to piece together (I think we all were!) why an event of this scale is not widely known about today. There were four to five million visitors since the festival opened in May 1911 and closed in October of the same year. The festival was advertised in newspapers all over the country and reported as a site of enjoyment for rich and poor. In addition to this, there was a lot of involvement of children and local communities as the festival overlapped with the coronation of King George V. It is clear that at the time there was a lot of effort to solidify the festival in the national collective memory. Following my research, I understood that along with the music and sporting events that took place there are aspects of the festival that are uncomfortable due to their close proximity to the Empire and thus are not often engaged with. For example, native people were placed in the recreations of traditional colonial settings. I then began to understand the wider importance of the project as not only a revisionist history of the event but a reminder that it happened and why it’s important!

I also began to consider the opportunities that the Art Assassins would have had to engage with material in formal education settings such as school or university. In my experience a detached and neutral approach is always recommended. So an equally important aspect of the project was creating a space that left room for emotional reaction to the material. Thus, before we began the digital work, we did a clay sculpture session. This was the Art Assassins first chance to respond to our research and start thinking about visual representations of our reactions. This project had a wide scope of outcomes which included Wikipedia edits and also our 3D world-scape. I think this is a great balance and has really allowed us to formulate both formal and informal responses to the exhibition. Within the world we can reflect our personal reactions, questions, and qualms but the Wikipedia editing challenges us to look past our own opinions and consider the facts of the festival to raise awareness of aspects that were previously neglected.

Harriet Vickers – March 2022

Co-researcher Sam Baraitser-Smith reflects below on his work with the Art Assassins to develop responses to the 1911 Festival of Empire research:

There was interest in the idea of a counter-festival or exhibition which could reference the design of the original event. The All Red Route, a tour by electric tram of dioramas depicting scenes from the ‘dominion countries’ was a major part of the Festival of Empire. We took this ‘guided tour’ format as a way of connecting artworks made by different members of the group in response to the Festival of Empire. A series of collages were made using texts and photographs from the festival, imperial propaganda reconfigured into oblique or contradictory messages.

In selecting materials from the archive, we gravitated towards what we identified as points of contradiction or unevenness within a carefully curated event. These included the fictional character ‘King Lud’, who featured in The Pageant of London, a staged history of the capital performed by over 15,000 volunteers. The character appears at the beginning of the pageant in a prehistoric scene depicting the founding of London. His fictional nature provided an opportunity for re-appropriation: he became the tour guide for the Art Assassins’ exhibition.

We also looked at the role of Black-British composer Samuel Coleridge Taylor, who conducted several performances at the opening of the festival. 11 years earlier, he had been the youngest delegate at the First Pan African conference in London, 1900. We discussed what assumptions could be made about a historical figure – if they could become a representative of conflicted or voiceless participants in the Imperial project.

The Art Assassins used modelling clay to sketch out their initial ideas: reimagined scenes from the pageant, characters and new festival installations. We later worked with Jazmin Morris at UAL’s Creative Computing Institute to realise the work using 3D modelling software. Components were modelled separately and then assembled in a virtual environment, where they could be displayed along with photographs, videos and audio.

Working in a virtual environment provided an opportunity to discuss how archives are traditionally presented to an audience. We examined the design of display furniture such as vitrines and cabinets, the architecture of museums and galleries, and systems of labelling and categorisation. We looked at installations by Mark Dion and Forensic Architecture, as well as the ‘cabinet of curiosities’: a form of private collection generally considered a precursor to the public museum.

The Festival of Empire tells us not just about how the British Empire projected itself on the world, but also the role of the arts and creative industries in facilitating this process, through design, performance, music and other disciplines. This projection of power through design and the arts is still evident in the staging of contemporary spectacular events such as the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony.

Sam Baraitser-Smith – April 2022

5 key moments from the Places Never Seen

Paul and Tommie run the Art Assassins, the South London Gallery’s young people’s forum for 14-21 year olds. They have been working on Places Never Seen: A Youth Led Investigation of the 1911 Festival of Empire since September 2021and found it to be an expansive and rewarding project. They had much to say about the Art Assassin’s exploration into the archive and digital worldbuilding but managed to pick out just five key moments to share here.

1. Crystal Palace Park Sculpture Tour with Invisible Palace

For the majority of the Art Assassins, the trip to Crystal Palace Park was their first time visiting the site. Seeing it in person really helped to contextualise the sheer scale of the 1911 Festival of Empire. We met Dawn and Sue from Invisible Palace, who led us on a tour of the mysterious sculptures that remain dotted around the park. The sculptures date back to the original Crystal Palace and the Great Exhibition, some have been moved around and others lost completely. Although there are no physical traces of the 1911 Festival in the park today, the Art Assassins were struck by the figurative sculptures that were intended to ‘represent’ different countries and continents. This echoed what Lucy Panesar had told us about how the 1911 Festival used art and design to celebrate Britain’s colonial conquests. Spending time with the sculptures and the discomforting context in which they were made, now standing in a busy park filled with families and joggers, sparked much debate and conversation amongst the group. This felt like an important moment; experiencing the legacies of British colonialism as a ghost in the present, not hidden away in a dusty archive.

2. What is an archive? Workshop with Iqbal Singh

Iqbal Singh, Regional Community Partnerships Manager at the National Archives, led a brilliant guest workshop for the Art Assassins at the South London Gallery. Iqbal introduced us to the fundamentals of archiving and the role of the National Archives. He also spoke about his work in theatre, sharing how creative practices can be used to approach sensitive subjects and give voice to those that have been marginalised. A highlight of the workshop was when Iqbal gave the Art Assassins a copy of a letter written by James Gillespi, a Jamaican sailor living in Barry in Wales, during the 1919 race riots. The Art Assassins analysed the letter, first in its original handwritten form, then as a typed transcription, and finally they listened to the letter read aloud by an actor. The activity showed us how the presentation of historic materials can vastly impact our interpretation of them. It also demonstrated the raw power of personal stories that can be unlocked when working with archives. Everyone in the room was moved by James Gillespi’s struggle.

3. Wikipedia training: Workshop with Lucy Panesar

An important part of the Places Never Seen project, was to equip Art Assassins with skills and knowledge to edit Wikipedia pages themselves. Lucy Panesar, Wikimedian-In-Residence at University of the Arts London and Stuart Prior from Wikimedia UK shared their expertise and led on this training. Lucy’s presentation emphasised the urgent need to diversify the Wikipedia editing community, highlighting the lack of women and young people currently involved, particularly those from global majority ethnicities. We all use Wikipedia in our everyday lives and anyone can become an editor. We need everyone’s voices to shape the information that is available on Wikipedia, not just a narrow few. In the workshop, we were surprised to find that many of the Art Assassins were unaware that Wikipedia was open to anyone to edit. An important takeaway for all was that there is a specific style of writing required for contributing to Wikipedia, a ‘neutral voice’. This became part of an ongoing wider conversation about working with materials relating to the 1911 Festival of Empire in our project. How can someone write neutrally about a subject when it is personally and emotionally charged. Why should they? How can we make space on Wikipedia for responses that go beyond the ‘neutral voice’?

4. Digital storytelling: Workshop with Jazmin Morris

Digital storytelling and world building was an important part of the Places Never Seen project. Jazmin Morris, a Computing Artist and Educator based at University of the Arts London, opened up a world of possibility by introducing Art Assassins to free digital online platforms including Tinker CAD and FrameVR. Jazmin’s expertise helped with technical instruction but also opened up conversations and thinking around issues of gender, race and power in digital technology. The session also gave the Art Assassins an insight into UAL’s Creative Computing Institute, a unique department in the university where students and researchers work with creative computer programming and coding. The workshops with Jazmin were key in helping to forge the idea for a collaborative ‘digital world’ created by the Art Assassins that became the main output of the project.

5. Digital world building

Following all of these incredible and rich workshops, the Art Assassins created a new immersive digital world on FrameVR. This virtual world tells the story of the Places Never Seen project and shared the group’s research into the 1911 Festival of Empire. The group split into teams to build sections of the world and were guided by researchers and Art Assassins alumni Harriet Vickers and Sam Baraitser Smith. The Art Assassins created a narrative journey based around their research, with the aim to bring audiences into the conversation through this digital platform. They decided to appropriate the ’All-Red Route’ as a way to guide visitors. The ’All-Red Route’ was a long-distance shipping route used by Royal Mail to carry post across the British colonies. In the 1911 Festival of Empire the All-Red Route was reimagined as a train ride attraction that transported members of the public through displays of the British territories. The Art Assassins own virtual world features all of the materials that came out of the project including collages, archive materials, 3D and clay sculptures.

Check it out for yourself here: Framevr.io/places-never-seen

This project was supported by The Audience Agency’s Digitally Democratising Archives project thanks to funding from DCMS and the National Lottery, as part of The National Lottery Heritage Fund’s, Digital Skills for Heritage initiative.