This Knowledge Exchange project looks at the 1911 Festival of Empire to develop understanding of Britain’s imperial past, what happened and what role the arts played in this, and what impact this had on the lives and lands of colonised peoples back then and the lasting legacy of this today. UAL Knowledge Exchange impact funding enabled project lead, Lucy Panesar, to complete the following activities as part of the first phase of the project between March and May 2021.

Editing Wikipedia

Funding enabled Lucy to collaborate with LCC Photojournalism and Documentary Photography student Lydia Wilks to edit the 1911 Festival of Empire Wikipedia page, adding context, more details of the festival exhibits and critical appraisal. Details of the edit can be found on the LCC Decolonising Wikipedia Network examples page.

Digital Revisualisation

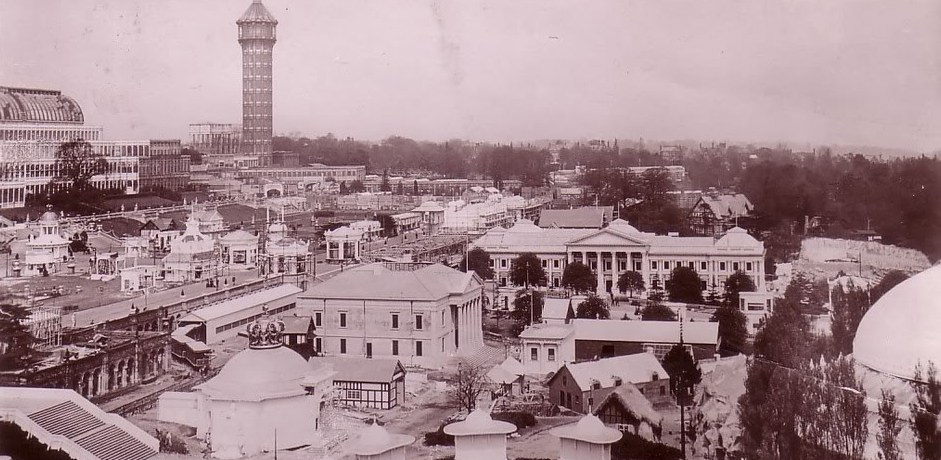

Funding was also used to support Crystal Palace Museum volunteer David Cardew to start digitally revisualising the 1911 Festival of Empire from archival materials, and share his work and skills at a workshop on 10 May attended by people from UAL and local community organisations. The work David started can be seen in Google SketchUp 3D Warehouse, and a screenshot below.

Project Roundtable

The remaining funds were used by Lucy to host a Project Roundtable event on 19 May with guest speakers exchanging knowledge of the 1911 Festival of Empire and perspectives on what significance this event has today. The event was moderated by Rahul Patel, UAL Associate Lecturer, Co-curator of Decolonising the Arts Curriculum zines and Co-leader of Decolonising Narratives reading group, and started with a presentation by Lucy Panesar and Lydia Wilks, after which the following six guest speakers were invited to offer insights and perspectives:

- Richard Watkins, Crystal Palace Museum trustee and tour guide on what we know and don’t know about the 1911 Festival of Empire from the Museum’s perspective

- Jane Collins, Professor of Theatre and Performance at Wimbledon College of Arts on Staging the Empire: scale and the performance of power.

- Oli Marshall, Creative Lead at Crystal Palace Bowl on the 1911 Festival of Empire Pageant and the relevance of past events in the reopening of the concert bowl

- Dr Dan Byrne-Smith, Senior Lecturer in Fine Art Theory at Chelsea College of Art on the ruins of Crystal Palace Park, spectacles of modernity and museums

- Dr Nicky Ryan, Dean of Design at London College of Communication on the role of the community in the development of Crystal Palace Park

- Wendy Cummins, Director of Radiate Festival on the Crystal Palace festivals, communities, and the Windrush generation.

A video recording on the event can be seen on YouTube here.

Staging the Empire: Scale and the Performance of Power

Guest post by Jane Collins, Professor of Theatre and Performance at Wimbledon College of Arts, University of the Arts London, 24th June 2021

The first thing you learn about writing for the stage is “the play takes place in the head of the audience”. I want to ponder briefly on the Festival of Empire from the perspective of its audience. To see it as a scenographic space that presents the audience with an apparently stable and detached point of view, allowing them to project themselves into the staged scenarios before them by “just looking”. However, just looking is a very complicated process:

What seems to be just “there to be seen” is, in fact re-routed through memory and fantasy, caught up in threads of the unconscious and entangled with the passions… More than that, seeing appears to alter the thing seen and to transform the one seeing, showing them to be profoundly intertwined in the event that is visuality. (Bleeker, 2008:2)

Just looking is in fact a complex web of sensory interactions and these interactions are themselves subject to different historic and cultural conditions.

What were the historic and cultural conditions of the audience in 1911? The audience of course was not a homogenised mass; it would have been sharply delineated along social and economic lines. London was a deeply divided city in the early twentieth century with abject poverty cheek by jowl with incredible wealth – much of it gained from colonial investment. The festival opened against the backdrop of Irish nationalism, striking dock workers and the women’s suffrage movement. In addition, confidence and belief in the ‘civilising mission’ of Empire was fading among certain sectors of the educated middle class. There was also a growing sense among some politicians that the ties that bound Empire were loosening, as independence movements continued to grow in India and South Africa; The African National Congress (ANC) was founded in 1912 just six months later. It was in this context that the British public were presented with a ‘celebration’ of trade and industry geared towards reinforcing in their minds the greatness of Britain and by association themselves as British subjects. So, what did they see?

They saw the Parliament buildings of many of the colonies but scaled down as three-quarter size replicas. Impressive but not overpowering. It is quite likely that this was a pragmatic decision on the part of the organisers to do with cost, but scale has a performative function in architecture, and these buildings were diminished. In the words of Lévi-Strauss:

Being smaller, the object as a whole seems less formidable. By being quantitively diminished, it seems to us qualitatively simplified. More exactly, this quantitative transposition extends and diversifies our power over a homologue of the thing, and by means of it the latter can be grasped, assessed and apprehended at a glance. (1962:16)

Likewise with the festival dioramas, where complex human interactions were simplified and laid out for the viewer to ‘just look at’ from the comfort of a specially built miniature railway. These model worlds seem to be unpopulated, apart from the Indian tea plantation, where a male manikin is very prominently featured wearing a lunghi. However, this ‘undressed’ figure in the eyes of the audience, presents the onlooker with ‘a spectacle within a spectacle’ (Erlmann, 1999:103) as clothes, in the form of westernised dress, would have been understood as symbols of progress, and their lack, a signal that more development was still required to bring this worker into the ‘civilised’ modern world.

In his extensive volume, Music , Modernity and the Global Imagination, German academic Veit Erlmann posits the idea of ‘the co-authoring of global identities as part and parcel of Imperial practice’ (1999:10). I’m stretching his argument here, but it seems to me, that the fictional or fake identities of the Empire manufactured for the festival, colluded in the construction or authoring of fake identities for the audience. These mutual fictional constructs: the inflated sense of British imperial power set against the diminution of the colonies – in terms of the scale models and unclothed figures – fed into each other with tragic consequences for both parties. How many of those young men across all social classes who visited the 1911 festival carried that inflated sense of their superior ‘Britishness’ with them into the trenches three years later? How many colonial citizens were also lost in those battles, believing they were part of a great British Empire worth dying for?

References

Bleeker, M.(2008). Visuality in the Theatre. The Locus of Looking, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Erlmann, V. (1999), Music , Modernity and the Global Imagination, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1962). The Savage Mind, trans. G.Weidenfield, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.